Minaret

2009-2011,

public project [not realised]

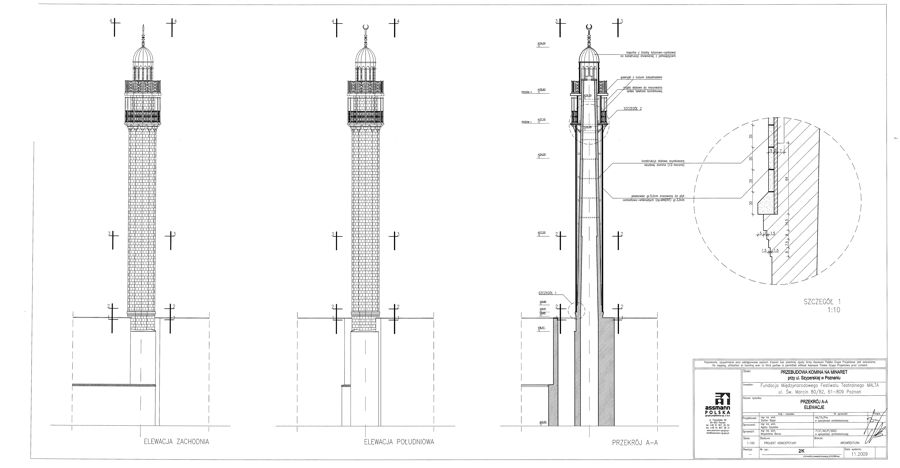

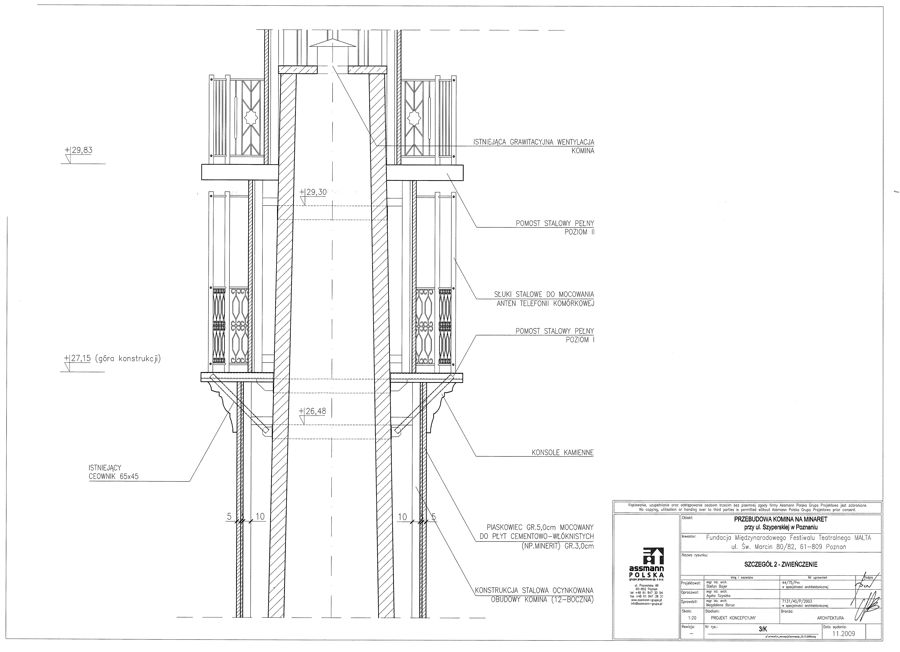

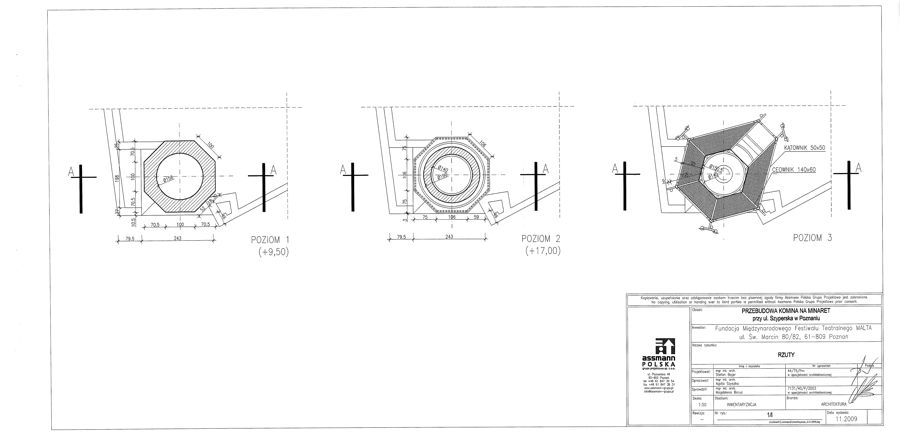

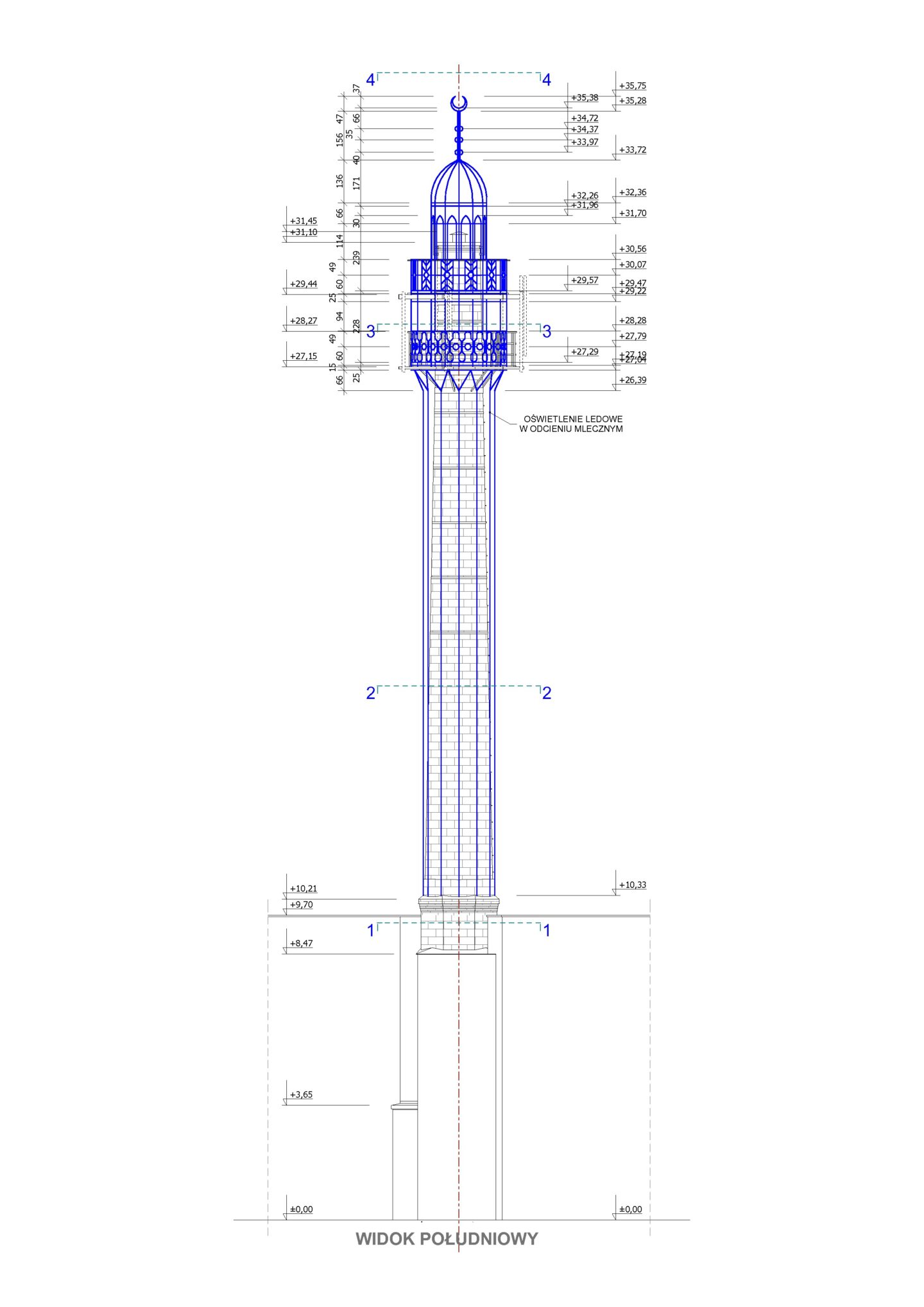

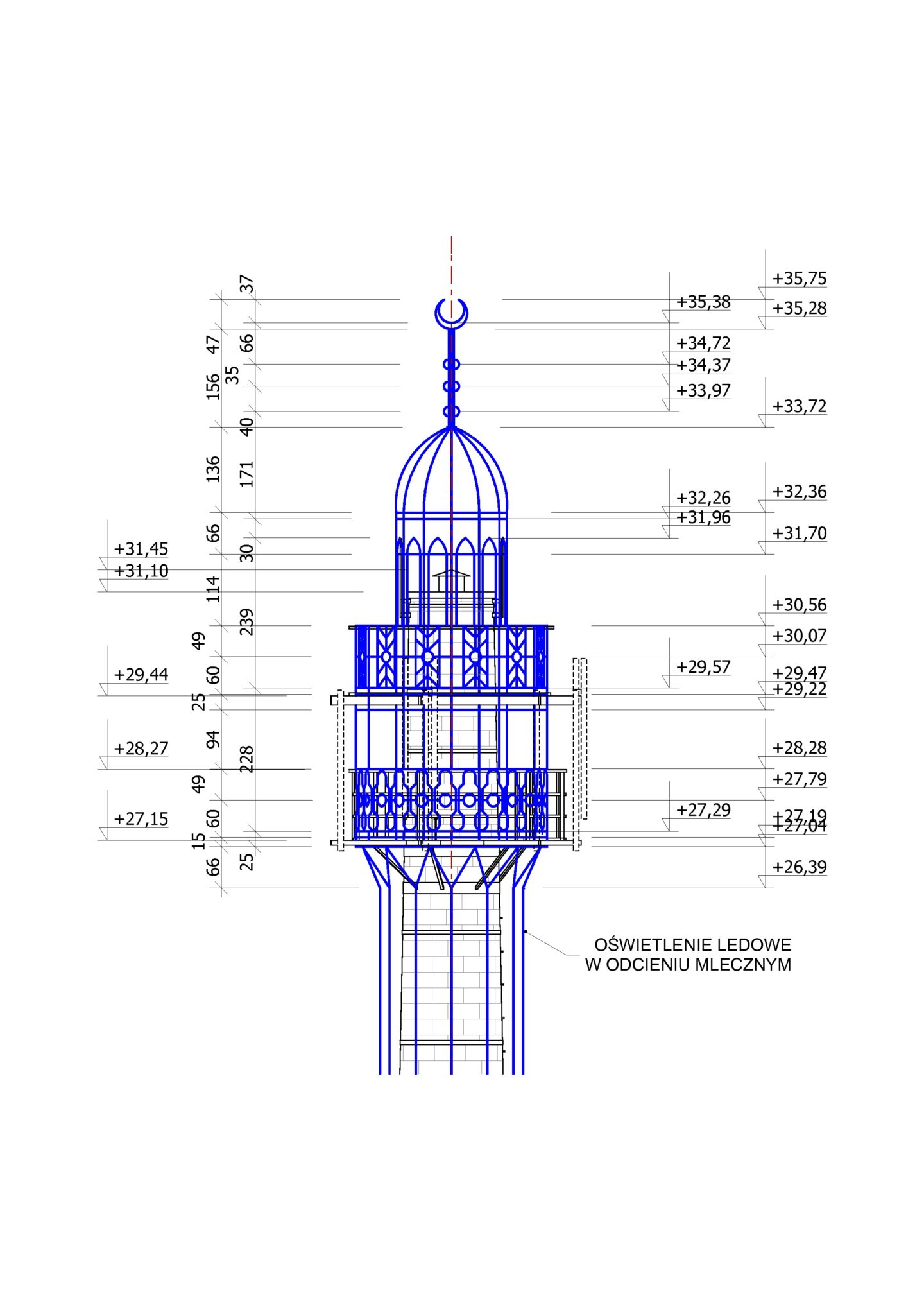

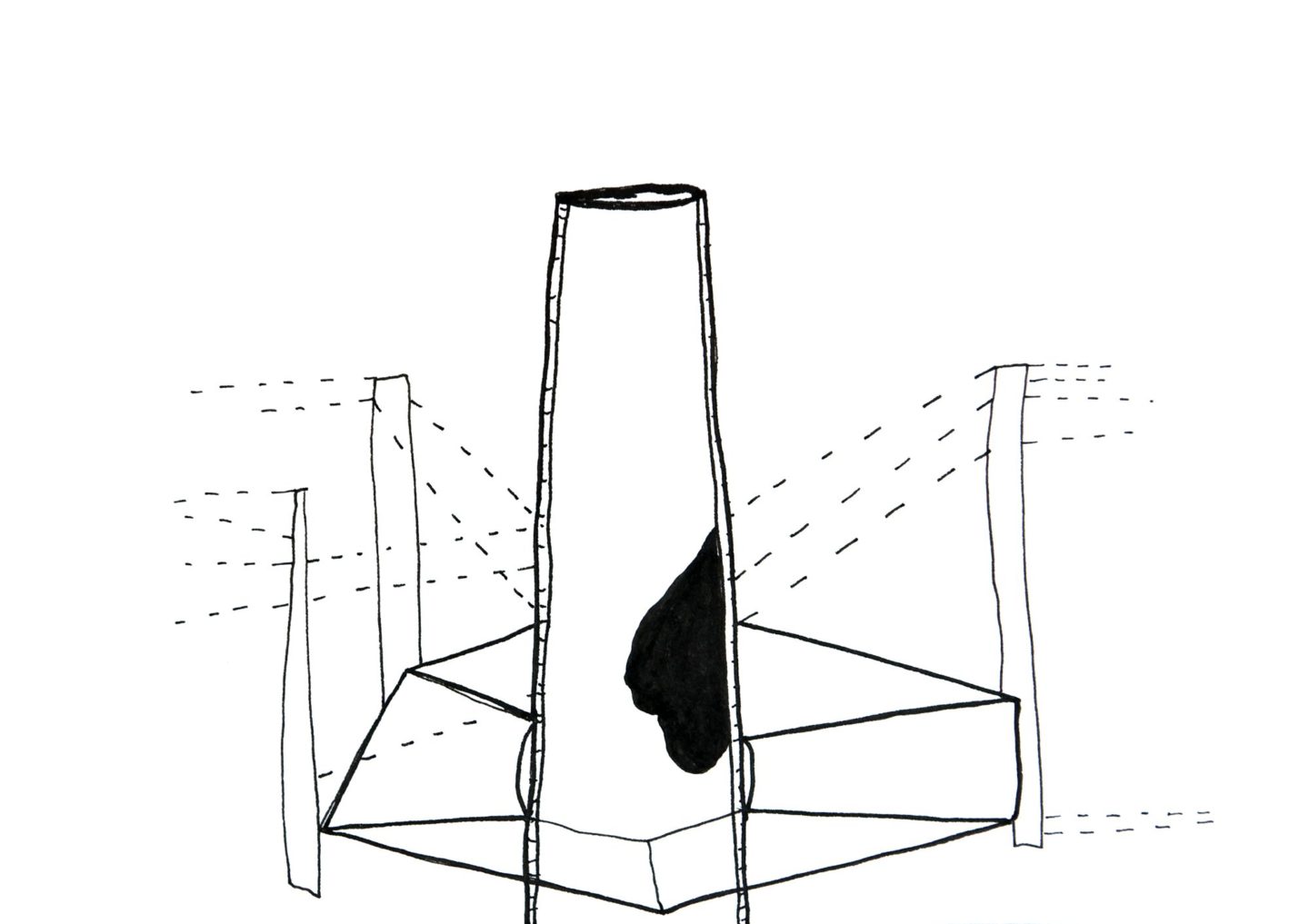

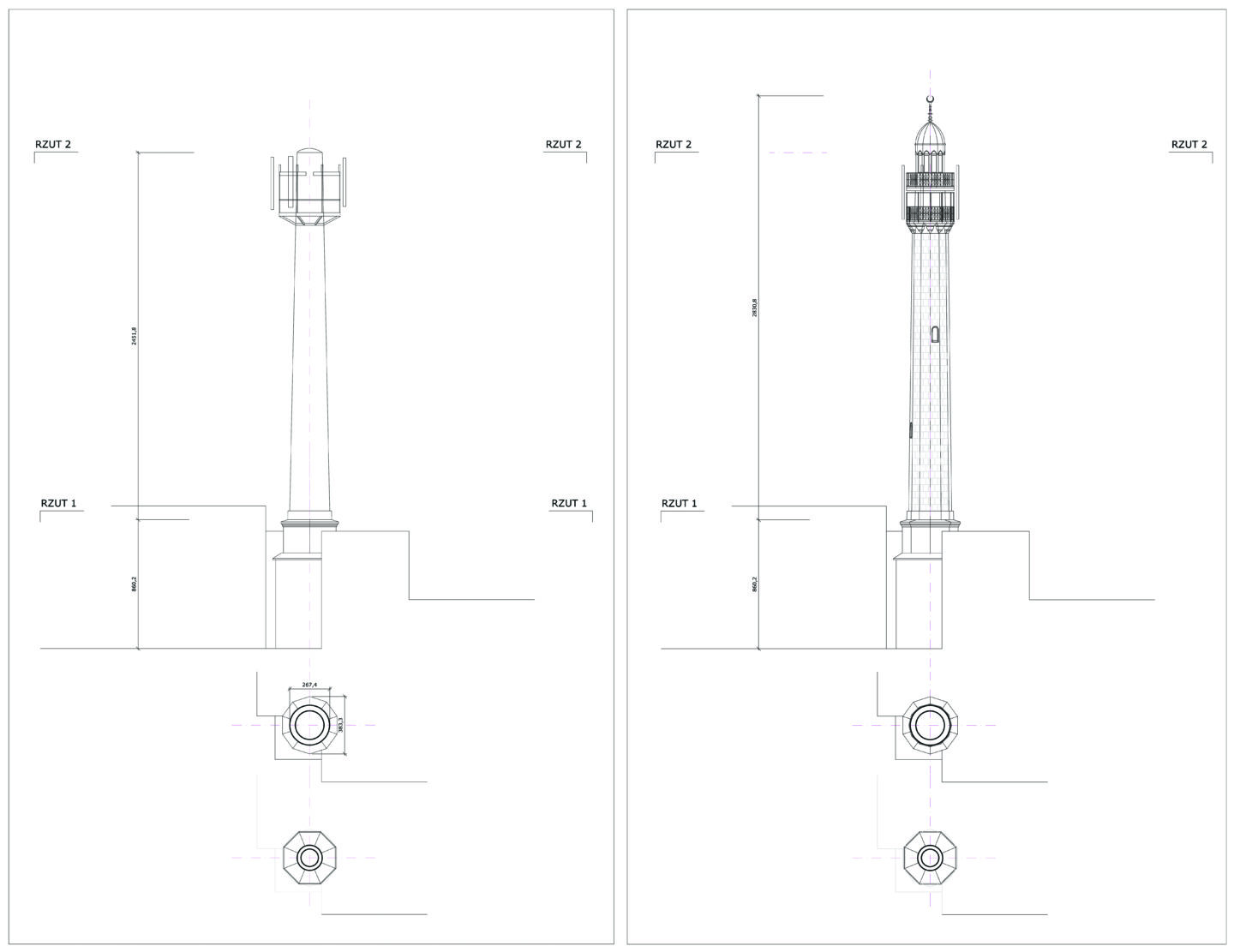

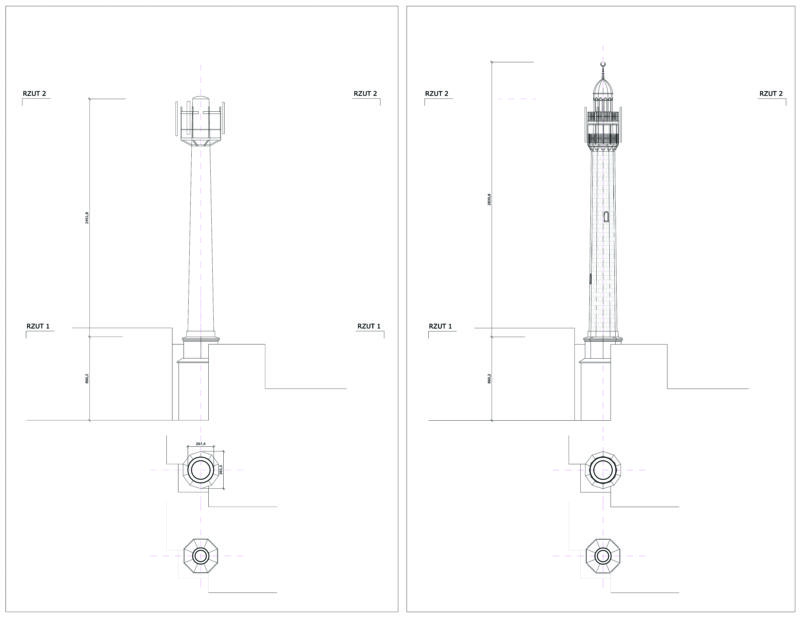

the disused chimney transformed into a minaret, at the crossing of ul. Estkowskiego and Garbary in Poznań, Poland

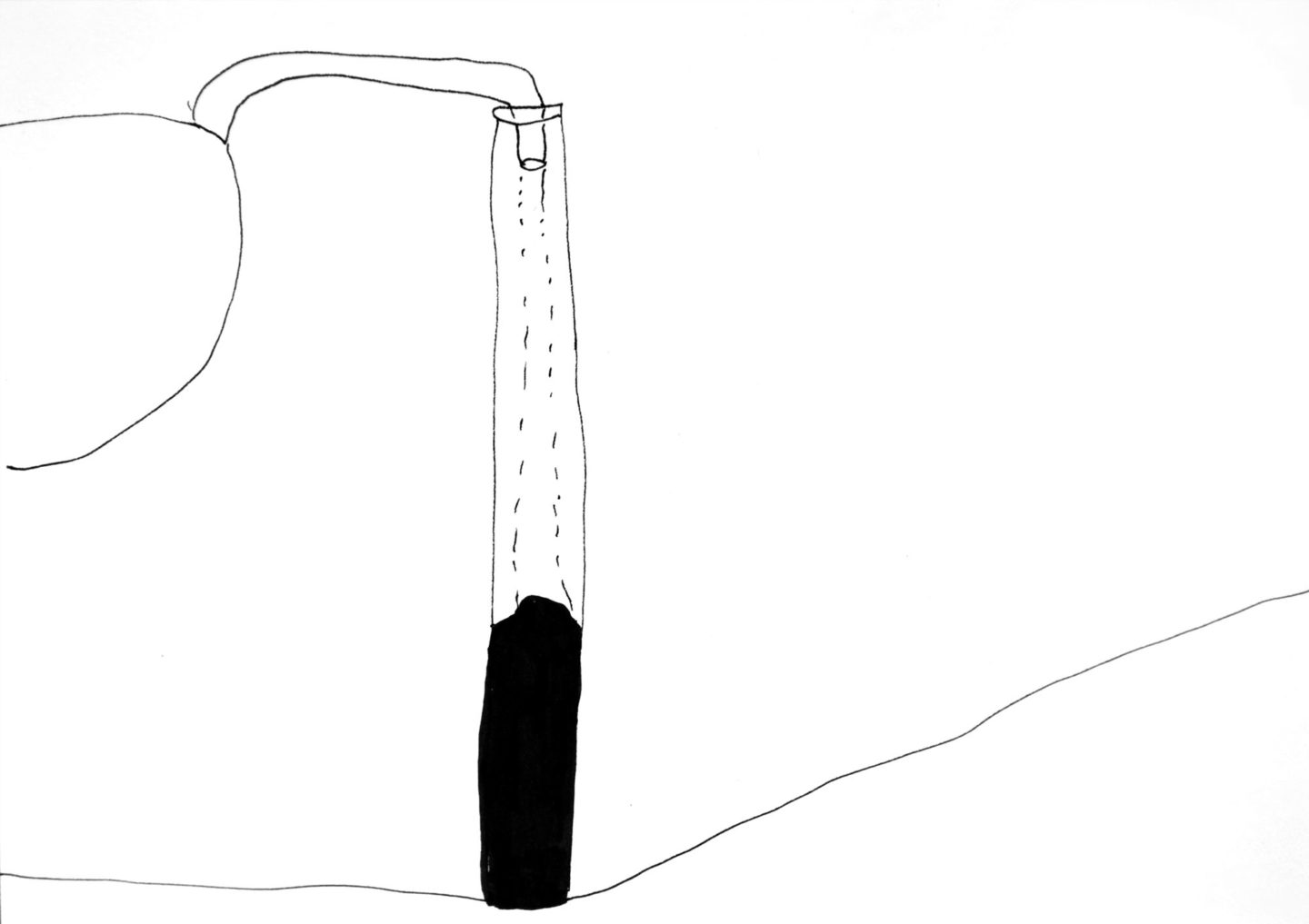

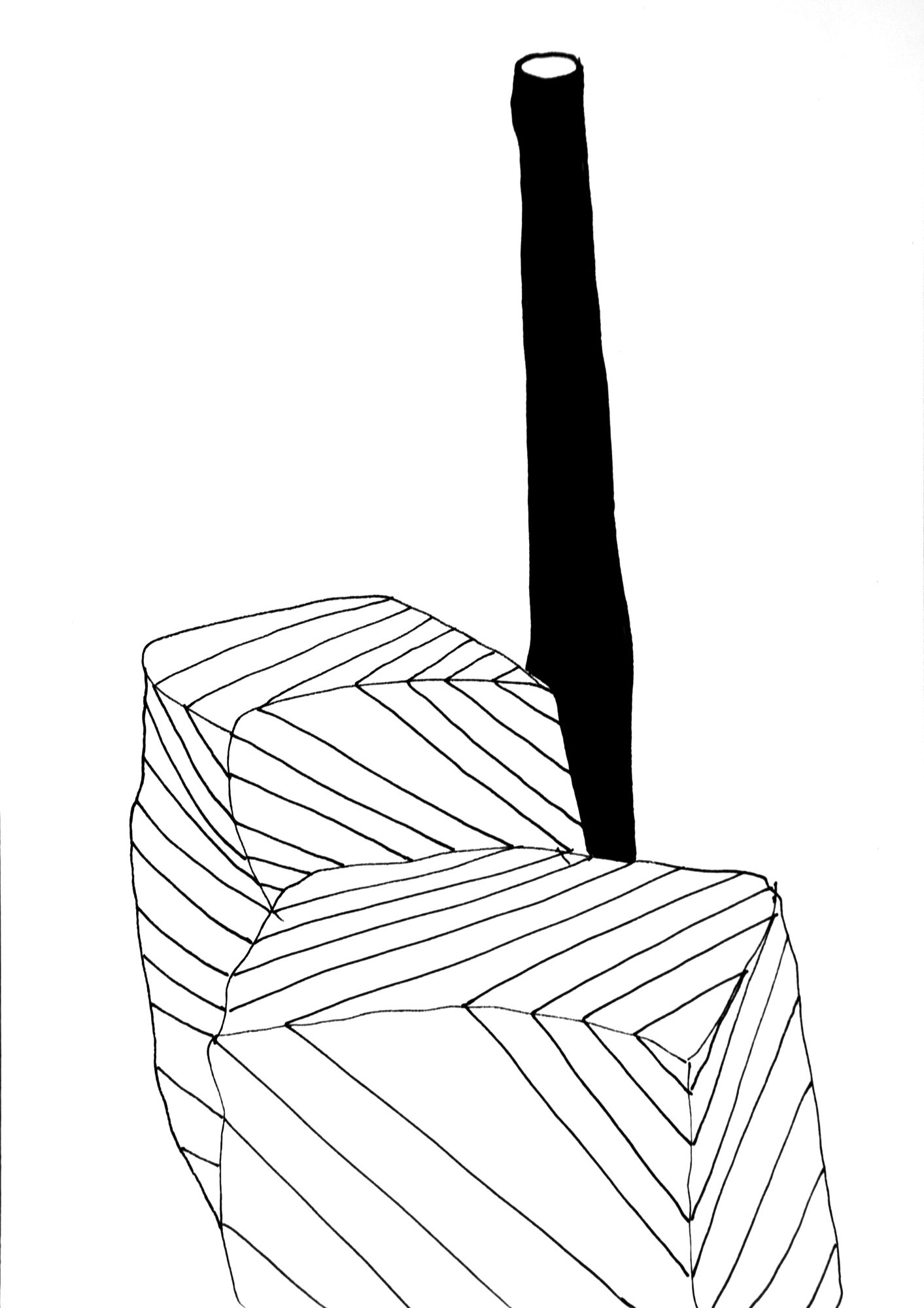

At ulica (street) Estkowskiego in Poznań, near the junction with Garbary, stand the pre-war buildings of a former paper mill. Today, occupants include the offices of the Fawor bakery, a toy wholesaler, and an Italian furniture store. Above the buildings towers a disused chimney, on which mobile phone transmitters have been installed. It is this chimney that is the axis of the Joanna Rajkowska project that would have it transformed into a minaret.

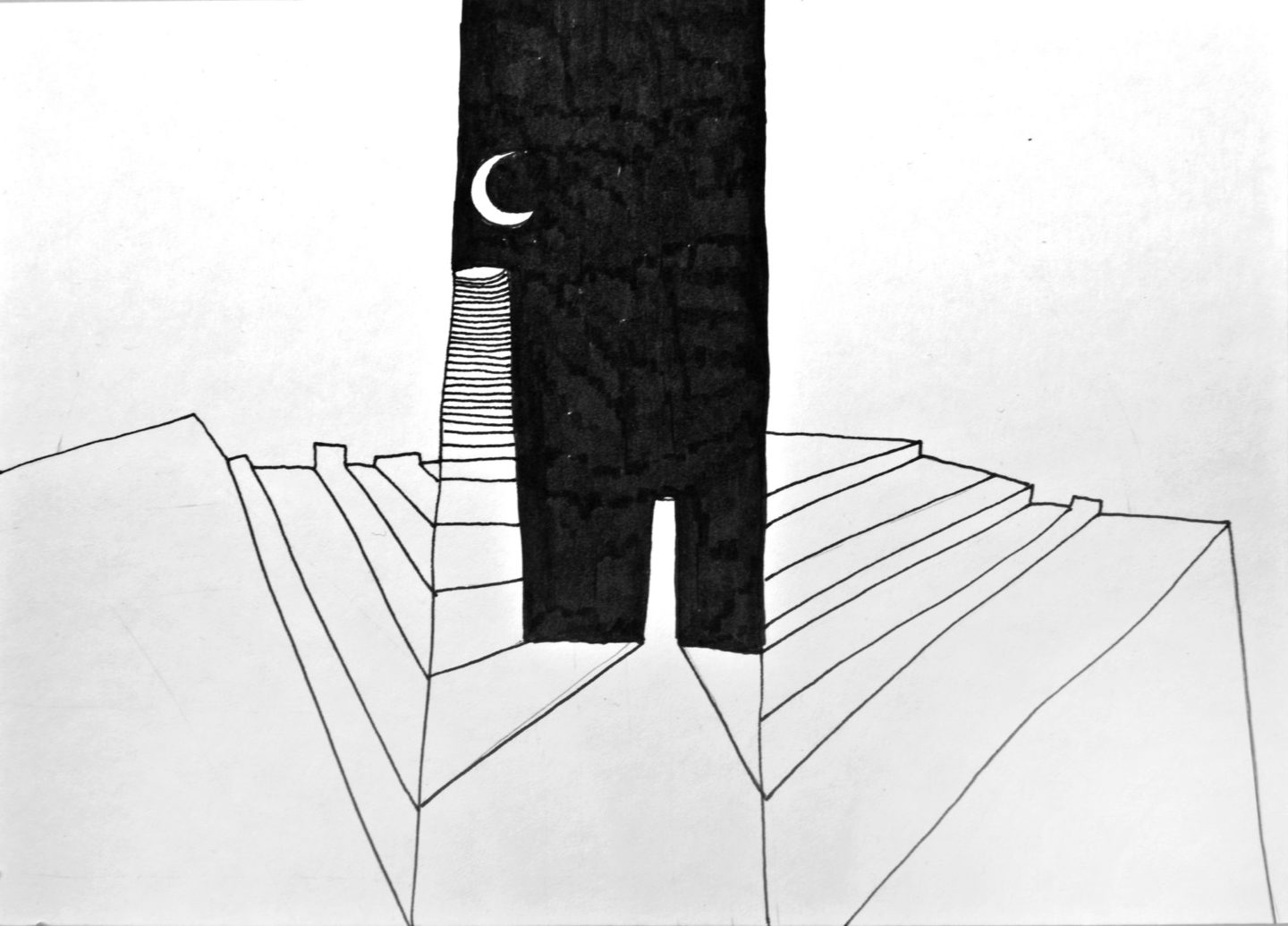

The chaotic layout of the buildings resembles a Middle Eastern city, especially the two blind walls facing the street. The place is located between Old Market Square and Ostrów Tumski, off the typical tourist trail, a bit out of the way, though very close to the city centre. It is one of those places that you pass on your way to somewhere else.

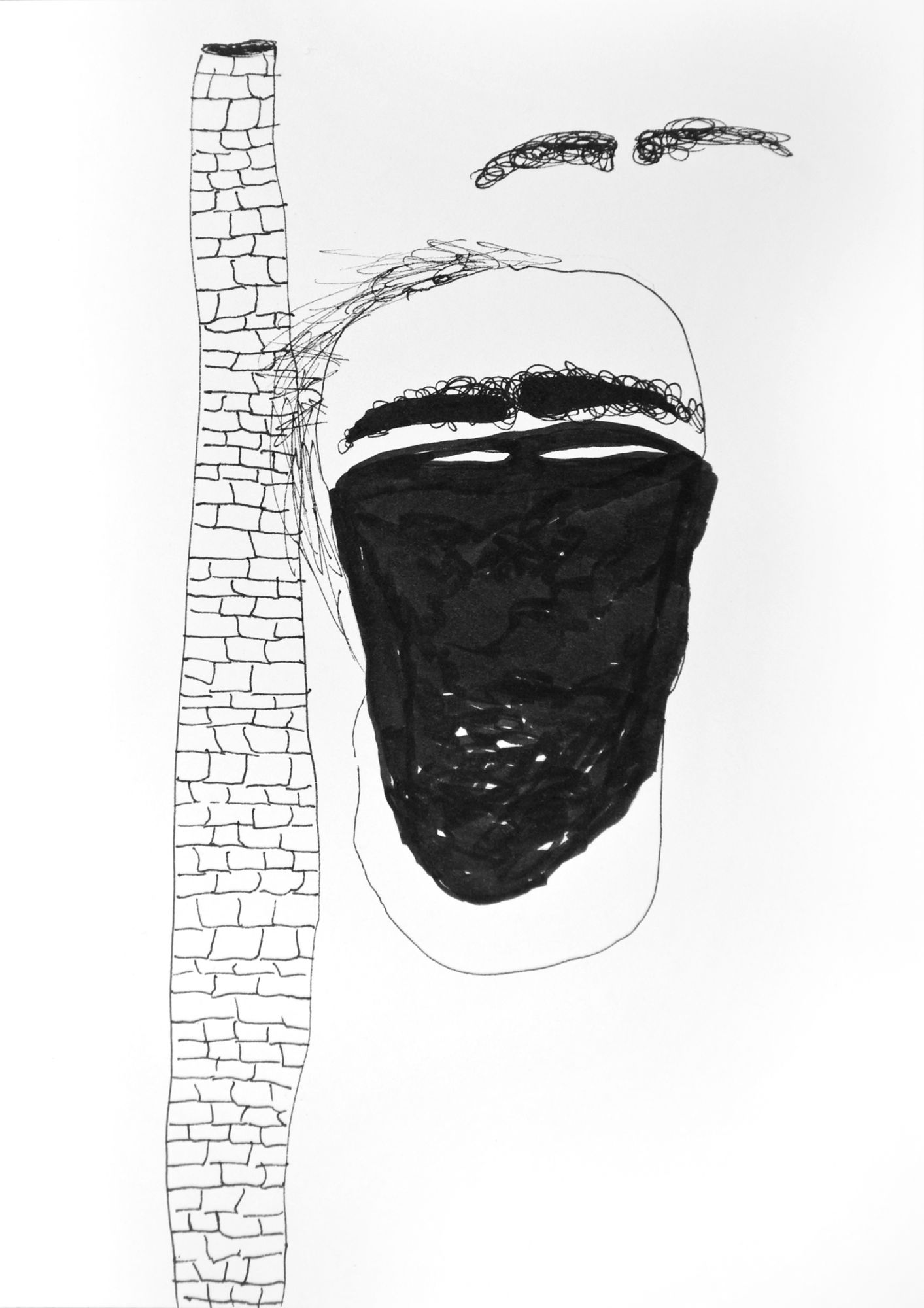

When you look from the junction of ul. Małe Garbary with ul. Bóżnicza, the bakery with the chimney loom beyond the former synagogue, and further away you see the two massive spires of the Ostrów Tumski cathedral. But this is by no means the only or the most important viewing axis. It is an important one, but still only one of the thousands of the possible viewing axes of the potential Minaret.

If the Minaret ever materialised, the character of the whole area would have change in a surreal manner. The familiar would have become strange. The red-brick buildings, the empty walls, the surrounding wall and the billboards would have presented themselves in a different way. One would have had to make an effort to recognise this place again, to understand and assimilate it. The Minaret would have given the whole area an exotic flair, and turned it into a Place. This Place would have been created by the tension between the familiar and the strange, the obvious and the puzzling.

Besides the obvious fact that it is not a genuine minaret but only its architectural symbol, the Minaret, like the minarets erected next to mosques, has no religious function of its own. ‘The minaret is just a building, it has no religious significance whatsoever’ [Messikh Mohamed Salah, leader of the Muslim League in Poznań, quoted after Gazeta Wyborcza, 30 June 2009].

Nor is it an expression of fascination with Islam by the artist. Rather, like the palm tree in Aleje Jerozolimskie in Warsaw, the Minaret asks where we – Poles – are in the process of opening ourselves towards strangers, aliens, people not from here. Why we have come to identify Islam with terrorism, what are the sources of our fear of Islam, and what image of Moslems we have created for ourselves. As well as why we silently agree to the presence of Polish troops in Iraq or Afghanistan, why we stand on one side with the aggressors, and why Poland became a place where the CIA had its secret prisons and rendition bases.

This project was not created in a contextual void. Poznań has a sizeable Moslem minority, estimated at about 1,000 people. The Minaret is also a question whether we, Poles, want to notice the presence of this minority – and how we do it.

Finally, the Minaret is an expression of an enchantment with the Middle East, the Orient, which for us, Europeans, has always been an area culturally both strange and familiar. Peregrinations to the East, starting with Chateaubriand and Lamartine, have always been more than just a romantic fascination. Returning from his famous journey to the East, with no money, just a small carpet from Cairo and a shisha, the Polish poet Juliusz Słowacki wrote that, ‘there is no reason to be afraid of the Eastern countries.’